Knowledge Translation in the ED: How to Get Evidence Used

The modern mantra of medicine is that assessments and interventions should be evidence-based. This means that new research should be incorporated into practice, and interventions that have not been demonstrated to work should be avoided.

There are very few physicians who would dispute this. However, with the volume of preclinical to clinical articles published every year, it is very difficult to read – let alone absorb – sufficient information to incorporate the latest and best evidence into urgent care.

There is a large gap between the recommendations of high-quality evidence-based guidelines and use of this evidence in routine patient care

Between 30% and 40% of patients do not receive care according to available, accepted guidelines. It is difficult to move research from the literature to textbooks, and it is just as hard to go from textbooks to widespread use.

For example, thrombolytic therapy was demonstrated to be effective in the early-mid 1970s. However, at that time it was either not mentioned or referred to as experimental in textbooks and reviews. There was a decade-long delay before thrombolytic treatment was taught as a routine therapy!

Knowledge translation is about helping doctors provide better care

Knowledge translation is the science of getting assessments, treatments, and techniques that have been demonstrated to work in peer-based literature out of the lab and into practical use. It seeks to:

- identify gaps between research and practice

- understand barriers to optimal evidence uptake

- develop strategies to achieve widespread use of best practices

There have been several barriers to the acceptance and implementation of evidence into patient care that have been identified. Most pressing are:

- lack of awareness of familiarity

- variable agreement (despite evidence to the contrary)

- questioning of self-efficacy and outcome

- inertia

These barriers apply even to widely accepted recommendations for patient treatment.

The Ottawa Ankle Rule: How a widely disseminated rule is used in practice

The OAR is a simple rule that can be applied to determine when an ankle or foot x-ray is required. For an ankle x-ray, it describes the three situations when an x-ray should be ordered.

A systematic review of 27 studies with 15,000 patients in 2003 found that the OAR was 100% sensitive in predicting which patients require ankle radiography and that the use of the OAR could decrease the number of ankle x-rays by 30% to 40%.

The OAR has existed since 1993, and it has been widely disseminated. However, according to a 2008 study, doctors struggle to apply it appropriately.

If there are difficulties in applying a simple rule such as the OAR, how can a physician be expected to apply a more complex rule at the end of a busy 10 hour shift?

Overcoming barriers to apply evidence at the bedside

To appropriately apply evidence, a physician must have several things:

- Ability to generate a focused question from variable clinical stimuli

- Knowledge of and access to appropriate database resources to answer the question

- Competency to critique available information

- An understanding of how to apply that information in clinical practice

Each of these requirements adds on a new level of complexity and cost as well as a demand for doctors’ time. For example, a physician has to know the relative merits of using Dynamed, articles from the American College of Emergency Physicians, and the Cochrane Library. He or she must also be able to wade through the evidence to discover the correct path forward.

Because of this complexity, while 40% of physicians are familiar with the Cochrane Database, only 15% have every applied it during clinical practice!

Doctors are willing to apply rules in the right circumstances

In a 2012 survey published in CJEM, over 90% of emergency practitioners reported that they would consider used clinical decision rules for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, and community-acquired pneumonia. Doctors are not using rules because they are difficult to remember and because they are not built into their workflow – not because they don’t see their value.

The question, then, is how to incorporate evidence-based decision making into clinical practice without disrupting physicians’ preferred workflow.

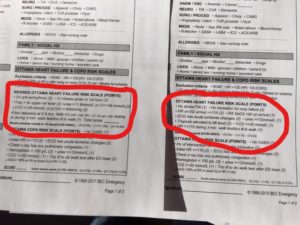

At BEC, we build clinical decision support into our templates and clinical content. This means that doctors have evidence in front of them while they chart. Using up to date practices is actually faster than avoiding them!

How knowledge translation is applied with BEC

BEC clinical content is a set of evidence-based templates for nurses and physicians. These templates are imported into a hospital’s EHR and customized to meet each site’s requirements. These templates are kept up to date to include the latest evidence.

Over 300 rules and guidelines are built into the documentation package, linking presenting complaints with an appropriate differential diagnosis list. Built in rules mean that up to date evidence is always in front of physicians. This lowers the likelihood of errors and speeds the selection of the correct diagnosis.

The package also provides evidence-based discharge prescription recommendations and discharge instructions that are linked to the diagnosis. These enable physicians to refer to evidence-based best practices at every stage of the assessment and treatment process.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post