How to make your EHR better

Doctors aren’t happy with their EHRs. That’s the conclusion of a recent RAND report (and brought to my attention by Dr. David More’s blog.

The study identifies several complaints about EHRs from the perspective of doctors who use them. According to the report, doctors perceive EHRs as hindering their ability to provide quality care, because:

- Using computers interferes with face to face discussions

- Doctors must spend too much time performing clerical work

- EHRs degrade the accuracy of medical records by encouraging template-generated notes

- There is poor EHR interoperability

As a result of these problems, 18% of doctors want to return to paper charting.

What is striking is that 82% of doctors do not want to return to paper charting, despite all the problems associated with many existing EHR systems!

Why is this the case? Probably because many doctors still see the potential benefits of EHRs. As a reminder, these include (according to healthit.gov):

- Improved quality and convenience of patient care

- Increased patient participation in their care

- Improved accuracy of diagnoses and health outcomes

- Improved care coordination

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings

The challenge, then, is to improve EHRs so they deliver their promised benefits.

Solving the problems with current EHRs

There is no silver bullet to eliminate the problems with current EHRs. However, three changes would make a huge difference and make your EHR better: workflow, workflow, and workflow.

Workflow #1: Build documentation so doctors can listen to patients

When I speak with doctors, a major complaint about EHRs (and some paper charts) is that it is hard to let patients talk about their complaints without having to immediately enter the data. The time required for typing means they must begin immediately, which means less interaction with patients.

For EHRs that allow dictation, this must be done away from the patient, which means that once documentation begins, interaction with patients ends. This delayed documentation also means that mistakes creep in.

Many EHRs also have charting on desktop computers. Again, when charting is done away from the patient, there is less doctor-patient interaction.

By using clinical content with flexible data entry options, physicians and nurses are able to talk to patients in the way that they prefer. For this reason, content in EHRs should not just be plain templates, but they should allow for the use of dictation, voice macros, and point and click templates. This content should also be available on either tablets or desktops.

EHRs must allow nurses and physicians to work as they prefer; practitioners should not have to change how they work to suit a computer system. EHRs – not nurses and doctors – are a tool.

Workflow #2: Build documentation that reduces clerical work

As discussed in a previous post, nurses and doctors are spending an inordinate amount of time on documentation – more than they’re spending on patient care. Without rehashing an entire post, it makes sense to implement decision support that decreases documentation time.

Going back to workflow #1, one way to reduce documentation time is to provide flexible data entry options. More important is to make sure the system works the way practitioners want them to, not the other way around. Again, more ways to reduce documentation time are in this post.

Workflow #3: Templates that work like practitioners

The drawback with most EHR templates is that they are too general and generic to be of any use; generic templates lead to generic notes, which is where the accuracy of documentation is reduced.

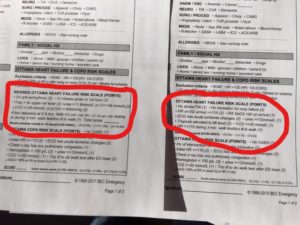

For example, I recently spoke with an emergency physician who was considering whether to use the templates that are built in to her hospital’s EHR system. The EHR system, provided by a major vendor, came with fewer than 20 templates. With fewer than 20 templates, physicians are practically using blank charts.

To allow detailed charting and useful decision support, templates should be at the complaint level. This means that every presenting complaint should have its own template. Further, templates should have different symptoms depending on the age and gender of the patient. Twenty complaints covers about 47% of emergency department visits.

To provide adequately detailed notes and useful clinical decision support, hundreds of templates are needed, with thousands of diagnoses.

Conclusion

Improving workflow with clinical content is not an EHR panacea. It is, however, an easy and low cost way to remove several of the barriers to EHRs providing health practitioners with efficiency and patient care benefits.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post